My work has long been about human relationships to place. How do these relationships define and sometimes change us? Several years ago, I set out alone to travel across the United States on a three-month photographic road trip. I would capture the landscape on film and make albumen silver prints (a photographic process popular in the mid-late 19th century) along the way. I envisioned myself following the proverbial path of photographers like Timothy O’Sullivan with his darkroom on wheels and Eadweard Muybridge with his mammoth plate camera documenting Yosemite. I created a modern equivalent of O’Sullivan’s portable darkroom- a custom built cabinet to fit perfectly in the hatchback of my Subaru, with compartments for chemistry, paper, and equipment. I outfitted myself with a monorail view camera and several lenses. I had no idea how much this experience would change me, my work, and my life philosophies.

As I drove, I spent a lot of time thinking about my place in the history of photography. While the medium has been much more accessible than say, painting, to women throughout its short history, this particular arena of photography has always been (and is still) vastly dominated by men. Perhaps this is because wandering out into the land takes a certain sense of adventure that girls so frequently are not encouraged to explore as children, or maybe it’s the physical demands of carrying a camera (though I do know of several women who are working in the landscape with significantly larger cameras than the one I use). What does it mean to be a woman conquering the landscape? I certainly don’t feel as though I have conquered it, more so, I feel reclaimed by the land and the places that are significant. I have a romantic relationship to place and landscape. Mount St Helens is my mother, Pikes Peak is my father, the Gulf Coast is my loyal friend, and the space between the Appalachian Mountains and the Chesapeake Bay is where my roots grow.

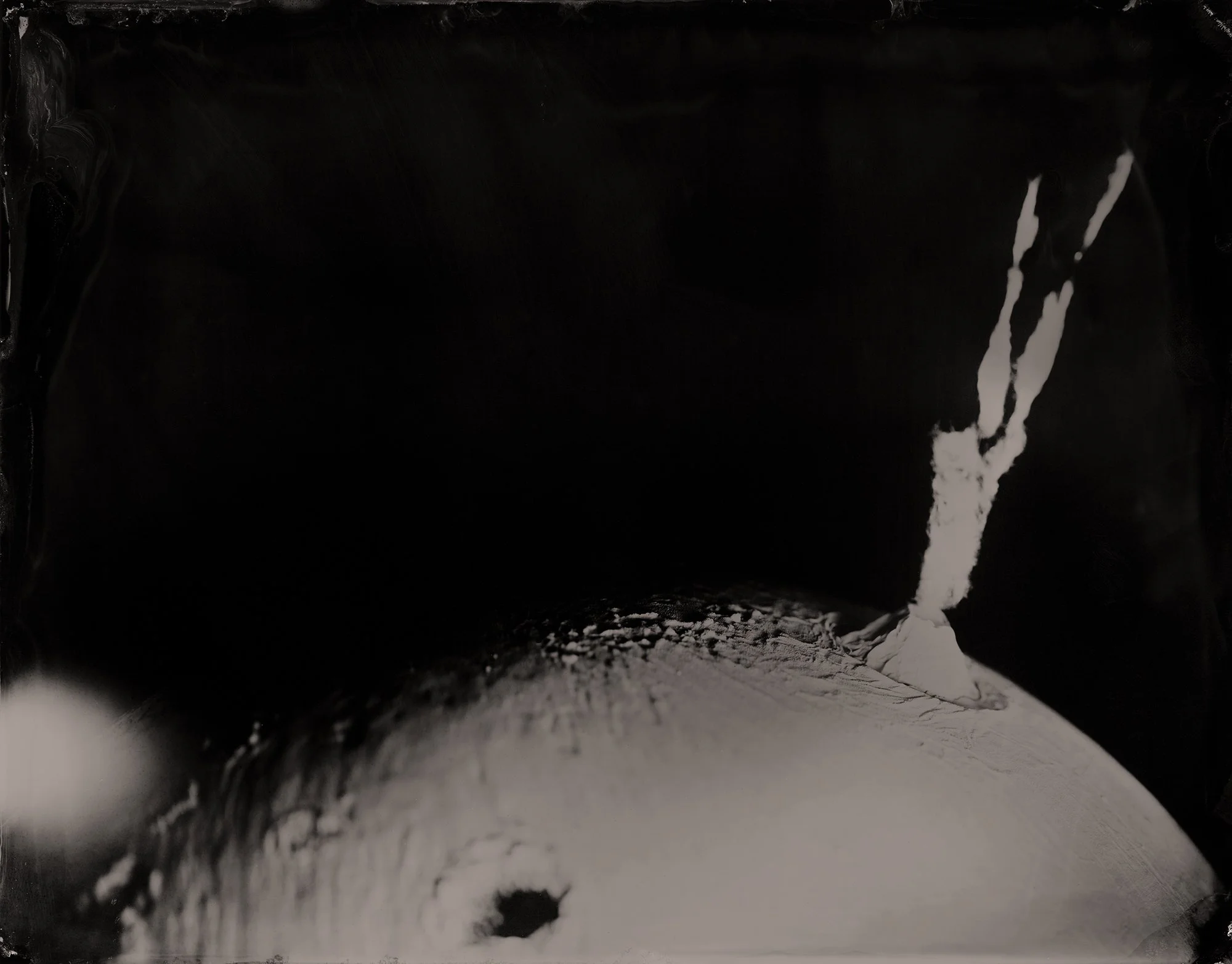

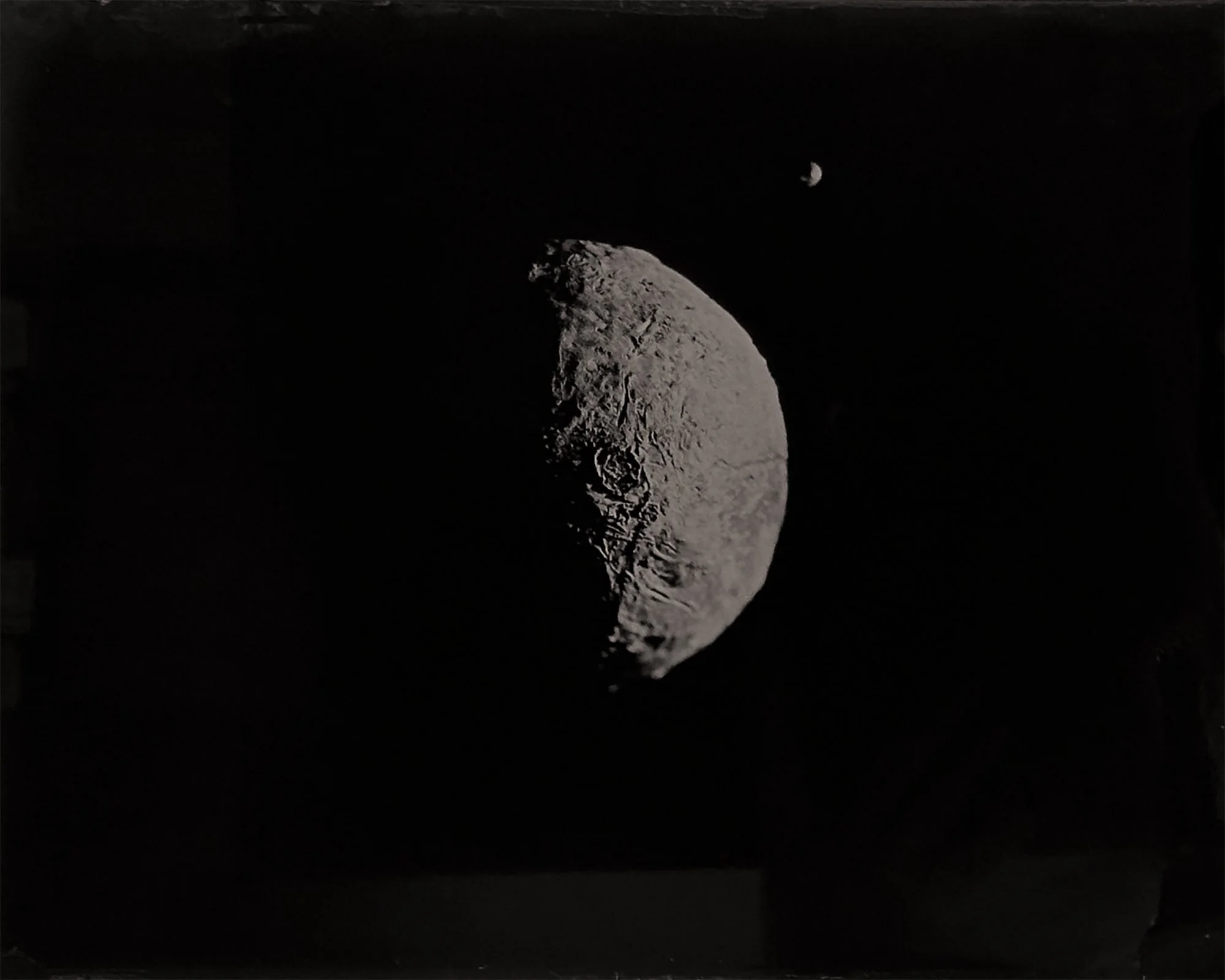

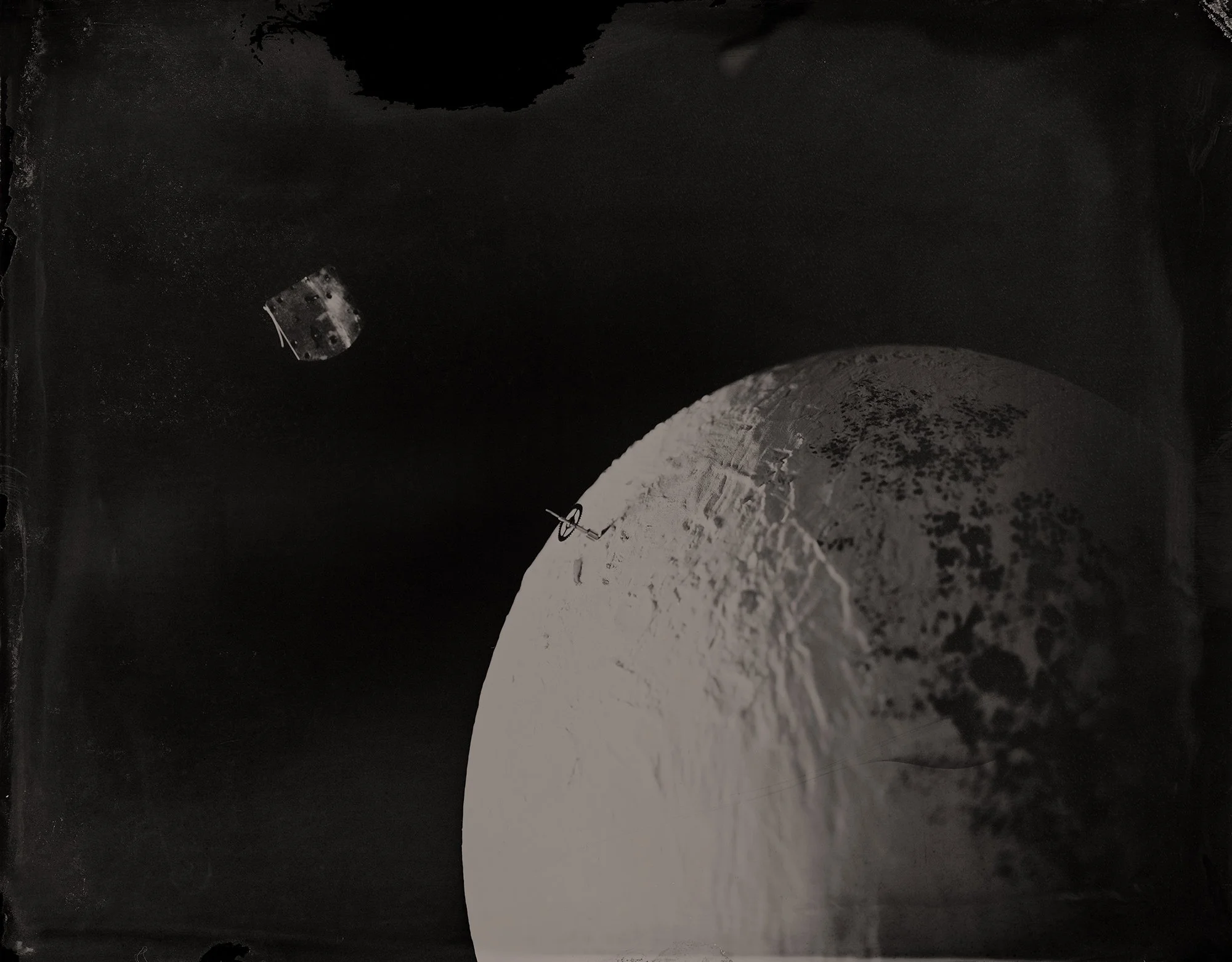

This romance with the landscape has blossomed to include a romance with process and with history. About three years ago, I began making wet plate collodion images. Both processes have an inherent romanticism to them. Through the wet plate process, my work has turned towards places we can’t see with the naked eye and our relationship to what might be. Through constructed still lifes, I am exploring fictional planetary worlds, early discovery, alchemy, and ideas of place and communication. Of course, I’m also thinking about early films like Le Voyage dans la Lune by George Méliès. My planetary bodies as large format wet plate images are tangible and yet fantastic. They all represent some sort of reality, but it is certainly a skewed reality. The images are of both place and time, yet… they are timeless. One of the most beautiful aspects of a wet plate is its luminosity. This glowing quality comes from the fact that the image itself is suspended in collodion above the surface of the aluminum plate or glass. Light passes through the collodion layer and bounces off the substrate, giving the image subtle backlighting. This is not lost on me as I am in the field or studio, under my dark cloth, watching the light, thinking... about place, about time, about history.

Check back for updates on this growing body of work.